What No One Tells You About HVAC & Lighting Integration

In a building, lighting and HVAC have historically remained separate systems without a need to communicate with one another. Although each of these systems have advanced in efficiency independently, there are additional energy efficiency synergies when they can be integrated.

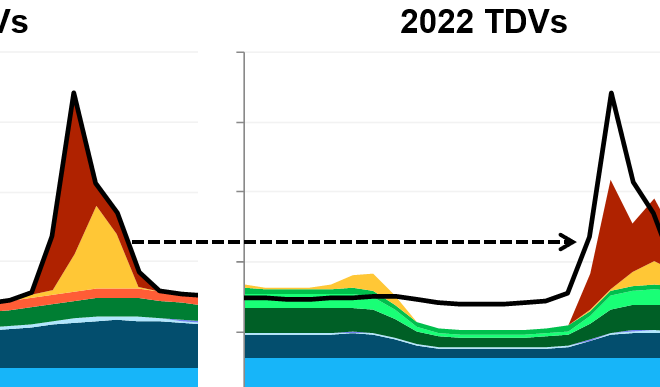

Recently, California’s 2019 Building Energy Efficiency Standards (Title 24 Part 6) have introduced a new mandatory requirement into code called “Occupied-Standby Mode” requiring many spaces to reduce HVAC ventilation to zero airflow when lighting or dedicated occupancy sensors detect the space is vacant (refer to Title 24, Part 6, Section 120.2(e)3). This simple concept sounds like a guaranteed Energy Efficiency Measure (EEM) with a lot of potential to save energy; however, successful implementation requires careful planning and coordination among disciplines, starting early in the design phase.

Since having completed commissioning on four buildings that have attempted to implement this, I would argue that it is not an easy process to reach a successful outcome, and, in some cases, the result was increased energy use. Despite this, with some relatively simple design considerations and coordination efforts, the “Occupied Standby” EEM’s energy saving potential is attainable.

Early Design: Describe the Design Intent for the Whole Team

The Basis of Design is a document created by the design team to capture the owner’s requirements concisely. This document is created in the early design phases and used to document the reasoning and decisions made. Because many design decisions occur throughout a project, this is a fluid document that requires updating. However, often, the updates to this document stop in mid to late design and do not carry through the construction phase. Designers should recognize that the audience for this document is not only the up-front owner but also the contractors, Commissioning Authority (CxA), and the building engineers that maintain the building. In a recent project, the controls contractor found an old system diagram of the HVAC intent only after completing the system programming and was amazed how insightful it was to his work. When created with the whole team in mind, the document is a powerful tool for communication and collaboration, increasing the chances for success, especially for systems requiring integration where it is necessary to explain the “why” behind the decisions.

Design Development: Coordination of HVAC and Lighting Control Zones

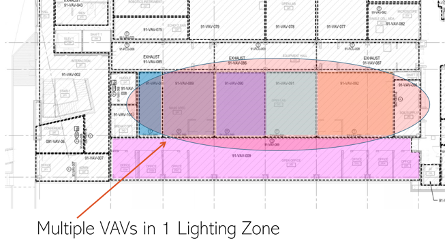

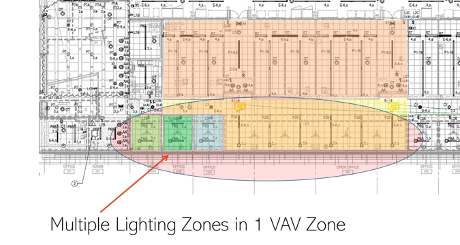

To set a building up for success, design teams should actively coordinate to define and determine control zones and zone maps between lighting and HVAC. A typical scenario often encountered is a single HVAC zone with one variable air volume (VAV) box serving multiple offices and a conference room, each have their own lighting occupancy sensors. In this scenario, the detection of occupancy in any one of those spaces will result in airflow to all. And since each space type has different variation in the occupancy rate throughout the day, it will most likely result in increased energy use due to the system requiring peak occupancy airflow even if some spaces are used intermittently. Identification of which occupancy sensors should be associated with each VAV box is needed. These issues can be addressed with additional coordination with lighting controls vendors and lighting designers by developing lighting zone drawings earlier in the process.

Construction Coordination: Who Connects the Systems? Identify Responsibilities

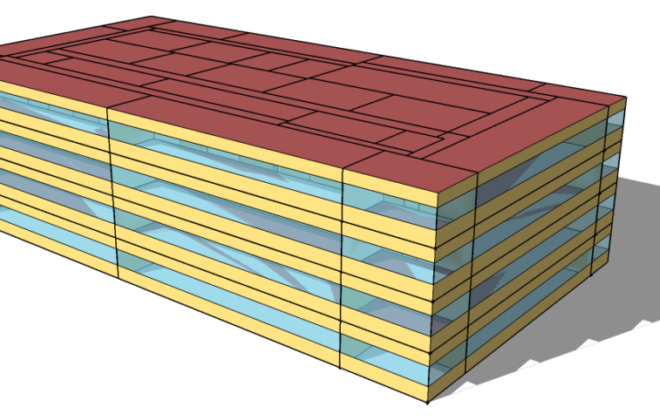

Multiple methods can be used to integrate the lighting and HVAC systems, depending on what lighting systems or technologies are specified. Whether it is a wireless device vs. hard-wired or cloud-based servers vs. local network controllers, these systems have an impact on the contractor’s responsibilities.

Typically, you have low voltage control wiring done by one contractor and higher voltage wiring done by another contractor. Yet the lighting control devices are low voltage, so who connects that wire?

The most likely outcome will be that each contractor believes it is the other discipline’s scope. Clearly defining the division of labor in the design specifications can help reduce problems with installation and operation. Successful integration fundamentally needs a dedicated person to champion the integration through design and construction; ideally a person who understands the intricacies of each trade. Currently, this role doesn’t exist on most projects. Still, some measures can be taken, such as selecting the controls contractor during the design process or involving the controls contractor in the early design phase to help identify specialization details and add more definition to the design documents. Additionally, project delivery methods like integrated project delivery (IPD), or other highly collaborative methods are opportune for this type of integration process.

On the Job: A roadmap is needed to get to the destination

The actual amalgamation of the HVAC and lighting system happens very late in the construction phase of a project, a time when project delays are met with fierce pushback. When the coordination of this issue gets left until these final stages of the project it creates significant schedule delays. The person who often takes the lead on integrating these systems is the controls contractor, who goes through a process of discovering the lighting points and importing them into the HVAC system. At the end of this step, the lighting points often show up as character strings that look like more like a foreign language, unrecognizable as to which occupancy sensing device is being identified. Currently, there is no standard naming convention for occupancy sensor identifiers or requirement to do so. The ability to identify each occupancy sensor is crucial since each sensor has to be mapped to the correct HVAC zone. Here are recommended steps to take in construction:

Step 1: Naming an occupancy sensor by project specific room number makes sense, but it needs to go even further. Often a room or area will have multiple sensors, for example, Room 204 sensor #1 vs. Room 204 sensor #5. Identifying multiple sensors within a given space requires a drawing with the device locations associated with the correct sensor names from the lighting vendor/contractor.

Step 2: At this point, the system controls are close, but most builders will still not have all the information needed for successful HVAC and lighting controls integration. Update and create as-built overlays of the lighting sensor locations over the HVAC zones. As previously mentioned, there will be areas where there are multiple occupancy sensors in one HVAC zone or there are multiple HVAC zones in a single lighting zone. Without a drawing with this information, the process of mapping the right lighting sensor to HVAC zone can take weeks to complete.

Step 3: The last step involves a bit of logic for grouping the occupancy points. For the case of multiple occupancy sensors in a single zone, if any one of those occupancy sensors is triggered, it should relay to the HVAC that the space is occupied. This requires some programming work to group these sensors together, and because this work can be completed in either the HVAC or lighting system, it often results in a disagreement of scope and additional costs in construction.

These common field installation problems could be addressed by creating design specifications that clearly describe the intent, scope, deliverables, operation required.

Lighting Systems need a Sequence of Operations (SOO) too!

Lighting system and controls can be configured in a multitude of ways, and with more complex, interconnected systems there is higher level of ambiguity for intended operation.

Integrating the lighting and HVAC system requires a precise sequence of operation that provides a detailed description of how the systems should operate together; without it, the system remains at the default settings. For example, the SOO should address how to deal with failures, like loss of communication between lighting and HVAC. Another example is the time delay between the two systems, such as, is there a lag in the communication network.

Be explicit on how the system should work in every mode of HVAC operation.

One real-life example I witnessed on a recent project was an occupancy sensor being triggered by a security guard during the building’s unoccupied hours. This resulted in the air handling unit running at full ventilation for several hours when it was not necessary. Conversely, in the scenario of a pre-purge mode, if there is no occupancy the system still needs to provide ventilation air. It’s imperative that details like this are discovered before the end of the project, when changes and corrections become exponentially more difficult to implement as originally intended. Having detailed controls sequences developed for controls contractor review during design is a way to catch these issues earlier.

Additional Requirements Needed

Vendor coordination and integrated testing requirements

Typically lighting controls programming is done by a lighting vendor, not the electrical contractor. The vendor’s primary objective is to program the lights, generally with little or no time spent helping integrate their system with the HVAC. Many vendors are not local and are on the job site intermittently. Without the lighting programmer’s or vendors’ participation, a CxA is unable to manipulate the system, correct an issue, or even get an explanation of how the system was configured or mapped. By making it a requirement for the manufacturer/vendor to be involved in specific activities in the construction schedule, including onsite functional testing with the CxA, these issues could be avoided.

Design engineering startup and troubleshooting requirements

Today’s systems have increased complexity, and because of the propriety nature of most lighting systems, a single team member can’t have all the expertise necessary to provide the level of quality assurance needed for most buildings. This is why commissioning is a collaborative process that requires a team of individuals to be involved from the beginning to the end of the project. Both electrical and HVAC engineers should recognize they are “key” team members on this team and include time and budget to support the commissioning process adequately.

Building whole systems training for operators

Many owners, building engineers and building staff are craving a much more comprehensive level of training, or system-level training. Typical training focuses on the specifics of a piece of equipment or system. While this is foundational what is truly needed is training on the design intent, how the installed equipment accomplishes this, or how these systems work together. This background information (Owner Project Requirement / Basis of Design) is necessary to provide context and knowledge to understand a much more sophisticated and integrated building. With that knowledge, any future modifications to the system that deviate from the intended design will be less likely to occur. In my estimation, the best person for this training role is the Engineer of Record, but this could also be accomplished via the CxA.

Robust documentation on intent and system capabilities of products selected

Unfortunately, today’s controls systems haven’t reached a level of standardization that results in seamless integration. To successfully advance the future of HVAC-Lighting system integration into projects, design professionals need to play an integral role. Many issues can be addressed by creating design documents that clearly describe the intent, scope, deliverables, operation, and training required.

Project Manager or Owner Recommendations

- Ask contract teams to speak to past experience with integrating building systems in their interview.

- Define the system integration responsibility to a dedicated contractor.

- Include a pre-construction controls contractor in design or require a peer review of the permit drawings for system integration with one.

- Require lighting vendors include a scope to provide on-site system integration testing.

- Require design engineers to update specifications to include additional requirements for integration.

- Require design engineers of record to be responsible for startup and testing.

- Request whole systems operational training be provided.

- Request system intent and system zone maps be updated as-built for operations team.

Design Engineer and Architecture Team Recommendations

- Include the design intent of building systems and operations in the basis of design.

- Update the design intent as a living document with drawings and specifications.

- Provide to contractors and trades as part of construction documents.

- Produce lighting controls and HVAC control zone maps as part of standard drawing packages

- Produce lighting SOO

- Produce HVAC SOO of the lighting integration points